Apple Cottage in Buckland Court, South Devon

The History

The word 'Hams' ('Hamms' in old English) means 'river meadows' and 'South Hams', in this context, means meadows south of Dartmoor. Slapton means 'slippery place', which is quite appropriate considering the many brooks & streams that provide the lush farmland of the area.

It is thought there were several settlements here during the Bronze Age and also a fort, rather grandly named, Slapton Castle during the Iron Age. The site is recorded in the Domesday Book as a manor with a population of 200 and belonging to the Bishop of Exeter.

Slapton village lies in a hollow about a half mile from the beach; sheltered by a low hill ridge and separated from the sea by the fresh-watered Slapton Ley. Its position has meant that, unlike the neighbouring villages of Torcross, Beesands and Hallsands, it was hidden from view to attackers from the sea in past centuries. Before the opening of the coast road along the shingle bank, in the last century, Slapton was only accessible along the narrow and winding lanes from inland; consequently, it has almost always been a peaceful place.

The peaceful existence was temporarily shattered in late 1943 by the announcement that Slapton and the surrounding area was to be evacuated completely to allow American troops to practice for the D-Day landings on the Normandy beaches. Some 750 families and all livestock in six parishes had to move out; some never to return. During the winter of 1943 and early spring of 1944, the area bounded by Torcross, Chillington, Sherford, East Allington, Blackawton and Strete was occupied by thousands of U.S. troops taking part in the ill-fated Exercise Tiger; the name given to the Normandy landings practice. The area was mined, bounded by barbed wire and patrolled by sentries. Such was the level of secrecy that few people, even in the surrounding villages, knew what was happening. Slapton sands was used because of its likeness to the beaches of Normandy. Many troops lost their lives from the live 'friendly' fire and a surprise attack by German E-boats.

One structural casualty was the Royal Sands Hotel. A stray dog triggered a series of mines which badly damaged the building. It was finished off by heavy fire, courtesy of the Royal Navy, during the exercises and was never rebuilt; the site is now the middle sands car park.

There are several reminders of those dark days to be seen in the locality; these include a memorial on the beach erected by the U.S. Government, now temporarily removed, a commemorative plaque displayed in Slapton village hall and a Sherman tank, raised from the sea bed by Ken Small in 1984, on display in the car park at Torcross.

Read more on Exercise Tiger | BBC News: Tragic D-Day exercise date marked

The address of the Exercise Tiger Association is P.O. Box 1050 Beach Haven, NJ 08008.

Exercise Tiger Links: Naval Historical Centre | Slapton Village Community Website | Exercise Tiger National Foundation

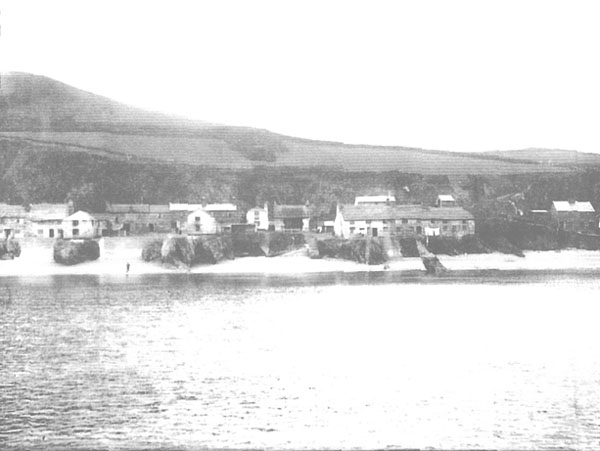

Hallsands was established in a precarious site sandwiched between cliffs and the sea. It grew as a fishing village during the eighteenth and nineteenth century, reaching a population of 159 by 1891. Its 37 houses were mainly owned by their occupants. A chapel has existed on the site since at least 1506 (ruins of the last chapel still perch on the edge of the cliffs today). Protected by its pebble beach, the village withstood the worst the sea was able to throw at it throughout the nineteenth century. Most families in Hallsands depended on fishing for a living, particularly crab fishing. It was a hazardous business, with earnings irregular, and frequent losses at sea. Everyone (including women) helped with the hauling in of boats and nets. It was a very close community.

In the 1890s, the Admiralty decided that the naval dockyard at Keyham, near Plymouth, should be expanded. The scale of the undertaking was vast, requiring hundreds of thousands of tons of concrete. In January 1896 the contract was awarded to Sir John Jackson Ltd, one of the country's largest engineering firms. In August of 1896 Sir John wrote to the Board of Trade requesting permission to dredge shingle from along the coast between Hallsands and neighbouring Beesands. Permission was granted on highly favourable terms, although the agreement did include a clause giving the Board the right to cancel the licence if they believed the dredging might threaten the shoreline.

Astonishing as it may seem today, no-one bothered to consult the villagers. As soon as the dredgers appeared, they protested to their M.P. - Col. Frank Mildmay. Mildmay, the Liberal Unionist M.P. for Totnes, was to become the villagers' most powerful ally in the struggle which followed. The fishermen protested because they were worried that it would; damage the crab pots, disturb the fish and most seriously, they feared that removal of shingle would lower the level of the beach, threatening their homes. Following a parliamentary question from Mildmay, the Board of Trade agreed to establish a local inquiry.

The first inquiry was held in June 1897 at the Hallsands Coastguard station. The conclusions tended to support Sir John, although it was recommended that the dredgers avoid the coast directly in front of Hallsands and neighbouring Beesands. In August an agreement was reached where Sir John would pay £125 a year to the community of Hallsands for as long as dredging continued he also agreed to pay for any damage to pots or fishing gear. For a couple of years after this, the fishermen appeared to have accepted the dredging without complaint.

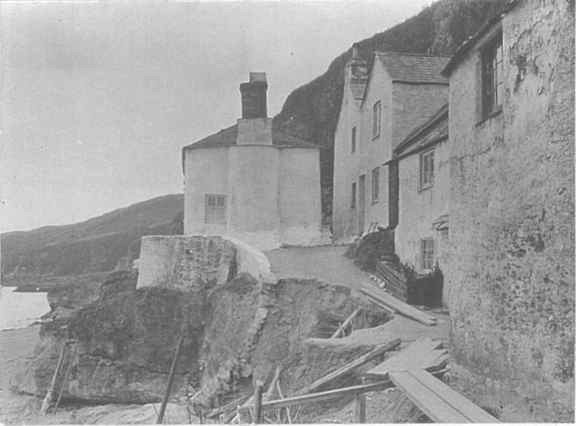

By 1900 it was becoming apparent that, as the fishermen had predicted, the level of the beach was falling. In the autumn storms the sea wall washed away part of the stone wall facing the beach. In November of 1900 property owners again petitioned their M.P. complaining of damage to their houses. Sir John replied to the Board of Trade denying responsibility but offering to pay for any damage attributable to his work during the dredging and for up to 6 months afterwards. The villagers did not respond, but in March 1901 Kingsbridge Rural District Council wrote to the Board complaining of damage to the road.

In September 1901 another report was held, this report concluded that the beach had fallen by 7 - 12 feet and "in the event of a heavy gale from the East ... few houses will not be flooded, if not seriously damaged." It concluded that dredging should be stopped. In responce the Board initially restricted the terms of the licence whilst Sir John tried in vain to negotiate with the villagers. On New Year's day 1902 they finally took the law into their own hands, preventing the dredgers from landing. On January 8th the licence was revoked.

During 1902 the level of the beach recovered, but it was to be short-lived. The winter of 1902/ brought more storms and damage.

In April 1903 the Board of Trade made a final offer of compensation of £3,000 (including £1,000 from Sir John Jackson), to which Col. Mildmay M.P. added £250 of his own money. The money was offered as a final settlement, requiring the villagers to sign away their rights to any future claim. Some of the money was used to compensate the owners of the houses which had been destroyed and for repairs to others. The remainder was used to build a new sea wall. A 1903 photograph shows the new wall and the extent to which the beach had fallen. Little remains of those walls today.

Behind the new walls, life returned to a kind of normality, although the loss of the beach made fishing more difficult. And the level of the beach was continuing to fall.

On January 26th 1917, a combination of easterly gales and exceptionally high tides breached Hallsands' defences. By the end of September 27th only one house remained habitable. Miraculously no-one was killed, but the villagers were now homeless. Eventually the villagers were offered £6,000 as compensation providing they signed as "full and final settlement".

The Cookworthy Museum of Rural Life in Kingsbridge (the nearest town to Hallsands) holds many of the relevant documents and photographs.